The First World War saw some 8.7 million men serve in the British Army at some point during the conflict. Of those, 5.4 million served on the Western Front (France and Flanders), which is where I suspect most people think of these men spending their time. But of course before they even got across the Channel a huge effort was necessary to recruit, mobilise and train such an army. Today the British Army is heading for a regular strength of 80,000, a tiny proportion of that First World organisation, yet I suspect that we all know of a military barracks in our local area and are aware of military activity. Thus imagine a one-hundred fold increase to the number of men under arms and the impact on the country’s infrastructure and landscape. Military camps and training areas grew up all over the country to cope with this expansion, and I will return to these shortly.

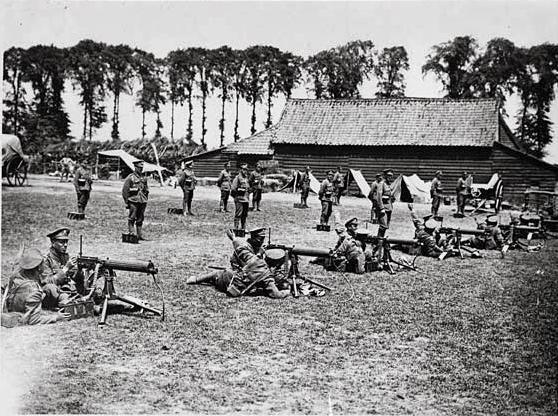

The First World War saw a step change in the manner in which war was conducted. Many will argue that it was the first industrial war; I might counter that by suggesting that the roots of the industrialisation of warfare were planted some fifty years earlier with the American Civil War, but that is a different debate. What is clear from the First World War is that many of the technologies that had been emerging over the previous fifty years came together with deadly efficiency during the conflict. The trench stalemate on the Western Front is usually put down to a combination of three things. First, the very effective defensive technology and techniques employed to create the trenches, and the use of barbed wire to make No Man’s Land impossible to cross safely. Second, the wholesale availability of tinned rations which meant that soldiers could occupy these defensive positions for weeks and month without having to forage off the land as they had in previous campaigns. And finally the rise of rapid firing weaponry making venturing into No Man’s Land a perilous activity. Crucial amongst this weaponry was the machine gun.

The first self-powered (recoil operated) machine gun had been invented in 1883 by Hiram Maxim (an American who moved to Britain in 1881). He conducted practical demonstrations in 1884, and his Maxim Gun was used by the British Army on colonial operations from 1893. In 1912 an improved version of his gun was produced by the Vickers Company and adopted by the British Army. It would remain in use through both World Wars finally being withdrawn from service in 1968.

Although having been around for some years, the machine gun really came to the fore in the First World War. At the start of the War all British Army infantry battalions were equipped with a machine gun section of two guns and this was increased to four in February 1915, as a result of the experience of combat in the early battles. But this experience also highlighted the need for bespoke tactics and organisation in order to make the most effective use of the weapon. As a result, in November 1914 a Machine Gun School at established in Wisques in France to train officers and machine gunners. This served two immediate purposes. First, to replace those personnel trained to use machine guns who had been killed or wounded, and second to increase the number of men with machine gun skills.

In September 1915 the War Office considered a plan to create a single specialist Machine Gun Company per infantry brigade, by withdrawing the machine guns and associated teams from the battalions, with the aim of fully exploiting this new technology. In order to give the battalions firepower they would be issued with the lighter and more portable Lewis machine gun. The plan was approved, the Machine Gun Corps was created in October 1915, and the companies formed in each brigade transferred into to the newly formed Corps. The reorganisation was rapid and was completed by the start of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. By the end of the war a total of 170,500 officers and men served in the Machine Gun Corps, of whom 62,049 were killed, wounded or missing.

In order to train and prepare these troops a Base Depot for the Corps was established at Camiers in France and a Machine Gun Training Centre was also established at Belton Park near Grantham in Lincolnshire, and it is this latter location that I will now focus upon.

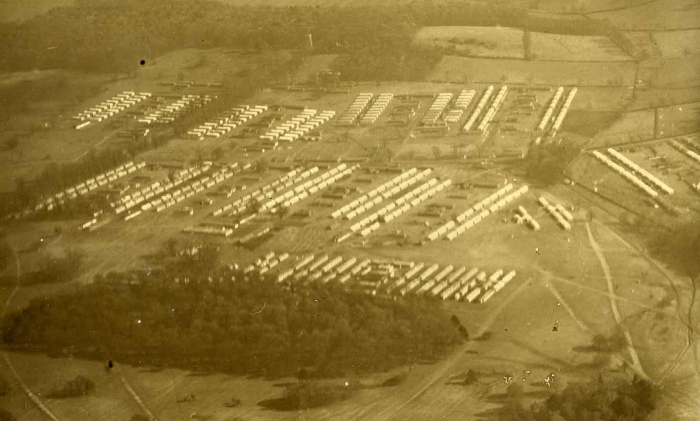

The camp at Belton Park came in to being shortly after the start of the First World War when the owner of Belton House, Earl Brownlow, offered the use of Belton Park to the War Office. A camp was begun in September 1914, firstly tented but very soon purpose built wooden huts were erected.

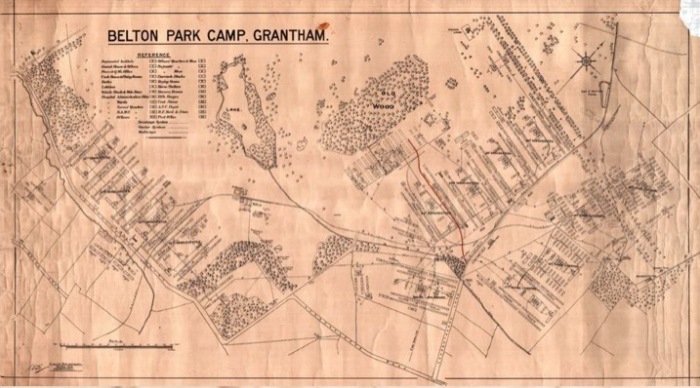

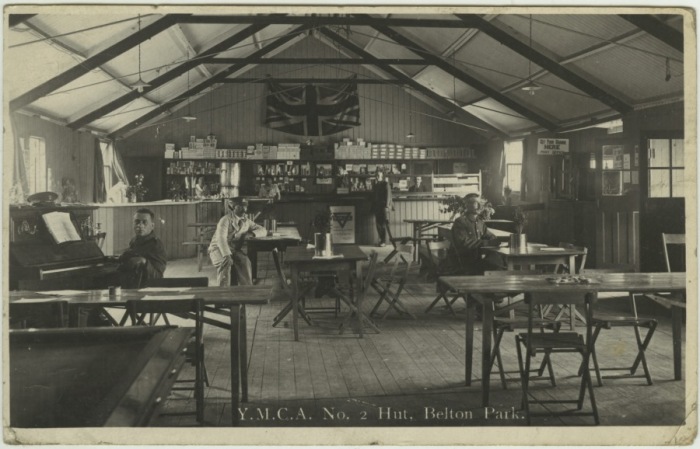

These burgeoned and the camp became a small town. It had some 840 wooden huts of which 500 were barrack rooms giving it a capacity of about 12,000 men and additional accommodation for officers, although some sources do suggest that the capacity could have been up to 20,000. It had its own 670 bed military hospital, 5 church rooms, 3 YMCA huts for recreation, a post office, a cinema and its own railway line. The map below gives an overview, but a more detailed sheet is available from the Belton House website.

The camp was initially occupied by troops of the 11th (Northern) Division, then by Pals battalion from Liverpool and Manchester who were part of the 30th Division, before finally becoming the Machine Gun Corps Training Centre on 18 October 1915 when Brigadier General Henry Cecil de la Montague Hill CB CMG took command of the camp. By November he had 230 officers, 3,123 men, 163 guns, 4 wagons and 60 cooks on site. The camp remained in place throughout the war and was eventually dismantled in 1920.

Today it is almost impossible to realise that such a huge encampment existed at Belton Park, unless you know about it. With the dismantling of the camp the land returned to its original use as the deer park for Belton House, and in the ensuing one hundred years almost all evidence of the camp has disappeared. Over the last few years, particularly with the First World War Centenary upon us, some interest has been rekindled in the site. In 2012 Episode 259 of the Channel 4 series ‘Time Team’ conducted an investigation on the site. The National Trust, today’s guardian of Belton Park, has also undertaken some investigative work to help interpret the scale and size of the camp.

I personally found out about this camp some years ago and have wandered over the landscape a number of times. There are just the odd clues to the camp if one looks carefully. The most obvious of these is a water tank, sited on top of the hill overlooking the camp site, and sitting alongside a much more prominent 18th Century folly. Constructed as part of the infrastructure to support the camp this simple round tank is one of the last remaining pieces of physical evidence of the camp.

As a result it is difficult these days, as one walks in the tranquil park land, to imagine the frenetic building that went on to construct the camp, and then the day to day noise and activity of thousands of soldiers undertaking training. The sounds of vehicles, horses, the shouting of orders and the rattle of gunfire as hundreds of machine guns were fired on the ranges purposely built for the job, (the target butts for which now form part of the local golf course) must have been constant.

With the dismantling of the camp the town of Grantham returned to peace and quiet, although it has become the home to a number of memorials to the Machine Gun Corps. The parish church of St Wulfram houses a memorial plaque and book of remembrance, whilst there is a stone tablet commemorating all members of the Machine Gun Corps on Belton Park’s Lion Gates. Finally in 2014 a new memorial, based on the badge of the Machine Gun Corps, was unveiled in Grantham’s Wyndham Park.

Now this story is of course not just about Grantham and its experience of the First World War, nor is it solely about the Machine Gun Corps, there is a wider point here. It wasn’t just Belton Park that experienced this phenomenon. There were hundreds of establishments growing up all over the country to house the rapid and enormous expansion of the British Army that took place in the first year of the War, and to deal with the casualties as they returned home. From Salisbury Plain to Cannock Chase, and from Manchester’s Heaton Park to as far away as Stobs Camp outside Hawick in Scotland, military establishments grew up all over the country. As I postulated at the start of this blog post, it is often easy to overlook the physical impact of the First World War at home, when the scale and horror of the Western Front (or the other theatres of war for that matter) dominate our First World War history and memory. Thus in this period of centenary commemorations it is interesting, and appropriate, to reflect on how this huge military footprint stretched right across Britain and the impact it had on the local economy, population and landscape throughout the country.

Thank you for posting this, it’s relevant to our family history, great to see the whole camp at Belton Park and read about how it operated on a day-to-day basis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello I live very near to belton park and often walk dog there. I always find it feels lonesome there…fascinating history of machine gun corps. Thanks for article

LikeLike

Hi Helen. Thanks for your interest and kind words.

LikeLike

I only know my grandad was there as it’s his address on my grandparent’s marriage certificate. They married in Sevenoaks. I don’t know why he was stationed there, but he must have been there at least 5 months as Gran was pregnant.

Fascinating insight into my Grandad’s life. Thank you.

LikeLike