This week the military history world has been focused on the centenary commemorations for the start of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. Less well commemorated, or as well-known I suspect, is the fact that 3 July 2016 is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadowa), itself an important and significant event, and the culmination of the short Austro-Prussian War of 1866, a war that would have a crucial role in shaping the Europe we know today.

The Austro-Prussian War, which was also known as the Seven Weeks’ War, was fought between the Austrian Empire and its German allies, and Kingdom of Prussia with its own German allies. At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 the German states were grouped in a loose confederation known as the ‘Deutscher Bund‘ and operating under Austrian leadership. As the nineteenth century progressed the conditions developed for a unification of the German states into a single Germany. Two different views emerged as to what that unification might look like. The first was a ‘Grossdeutschland’ or greater Germany that would see a multi-national empire including Austria. The alternative a ‘Kleindeutschland’ or lesser Germany would exclude Austria and as a result would be dominated by Prussia, the largest and most powerful of the German states, unsurprisingly the latter was the preferred option in Prussia.

When Otto von Bismarck became Minister President of Prussia in 1862 he immediately began to develop a strategy for uniting Germany as a ‘Kleindeutschland’ under Prussian rule. He first raised German national consciousness by convincing Austria to join Prussia in the Second Schleswig War. This swift and brutal conflict put the Danish provinces of Schleswig and Holstein under joint Austrian and Prussian rule. But very quickly after the conclusion of that war Bismarck provoked a further conflict over the administration of the conquered provinces, which resulted in Austria declaring war on Prussia and calling on the armies of the minor German states to join them, in what was ostensibly action by the German Confederation against Prussia to restore Prussia’s obedience to the Confederation.

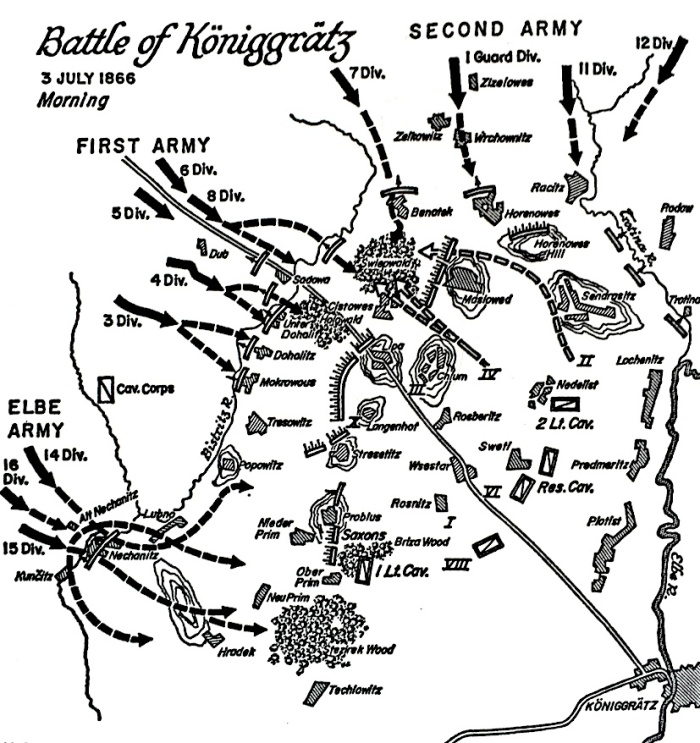

The main campaign of the war took place in Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic). The Prussian Chief of the General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke, had decided that the key to success was to ignore the minor German states allied with Austria, and instead concentrate on decisively defeating Austria itself. He planned the war in meticulous detail, rapidly mobilising the Prussian Army and advanced across the border into Saxony and Bohemia in June 1866 to confront the Austrian Army, which was concentrating for an invasion of Silesia. Moving rapidly, the Prussian forces were divided into three armies: The Army of the Elbe under General Karl Eberhard Herwarth von Bittenfeld, the First Army under Prince Friedrich Karl, and the Second Army under Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm. All were under the nominal command of Prussia’s King Wilhelm I, but in reality operational command sat with von Moltke. As the armies advanced, each on their own axis, they overcame Austrian attempts to stop them and by 2 July the main Austria Army had been sighted, encamped on high ground between the towns of Königgrätz and Sadowa.

Von Moltke immediately saw the opportunity to encircle the Austrians. He gave orders for Prince Friedrich Karl and the First Army to move forward and in conjunction with the Army of the Elbe to attack the Austrian positions across the Bistritz River the following day, 3 July 1866. He also ordered the Second Army, at this time some way off to the North East, to move in support with the aim of surrounding the Austrian forces.

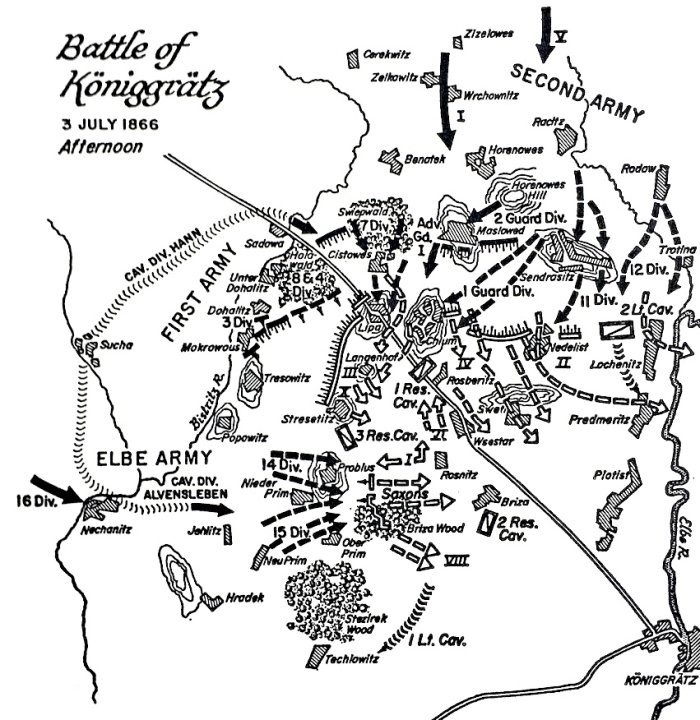

Moltke had intended the battle to be a textbook ‘pocket battle’ in which he would encircle and destroy the Austrian Army, but the weather on 3 July almost ruined his plans. As the First Army and the Army of the Elbe approached they were caught in the heavy rain and arrived wet and exhausted. Meanwhile the Second Army did not reach the field until late afternoon. The Austria commander, Ludwig von Benedek, therefore had the advantage of numerical superiority for much of the day with his 240,000 troops actually only facing 135,000 Prussians. Unfortunately for Austria he did not exploit this advantage.

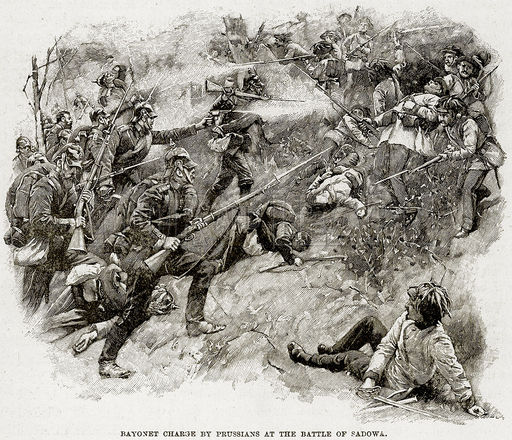

The initial Prussian attacks came from the Army of the Elbe in the West and the First Army in the North West. In the West the early attacks were successful and the Saxon Army Corps holding this portion of the Austrian defensive line were pushed back. They withdrew to new defensive positions and once there started to pour heavy fire on the Prussians bringing them to a standstill. Further north the Prussian forces started well and made good progress and an hour into the battle the town of Sadowa was taken, but soon afterwards the advance began to slow down under heavy Austrian fire. A considerable amount of this was coming from a wooded area called the Sweipwald in which Austrian troops were concealed. The Prussians attacked and the wood was cleared. The Austrians counter-attacked but their efforts were uncoordinated and confused allowing the Prussians to decimate the disorientated columns of Austrian infantry moving in and out of the wood. The Austrian position was not helped by paralysis, indecision and confusion amongst the Austrian command. Benedek stopped an attempt by a subordinate (General Anton von Mollinary) to swing the Austrian Army’s right wing forward to encircle the two Prussian armies at Sadowa before the arrival of the third, losing a valuable opportunity and creating chaos in the field.

Aided by Benedek’s inaction, Moltke had time to wait for the arrival of the Prussian Second Army which he was finally able to commit late in the afternoon and it struck Benedek’s weak right flank. With the assault now on all sides the Austrian Army began to disintegrate. Gallant but futile rearguard actions took place to slow the Prussian advance. One lone horse artillery battery, under the command of Captain August von der Groeben, tried to stem the Prussian advance. Its desperate salvos were answered with crippling Prussian fire from all sides and within five minutes Groeben, 53 men and 68 horses were all dead. This was followed by the Austrian cavalry which charged into the pursuing Prussians. For half an hour the they succeeded in holding the Prussian cavalry and pushing their infantry back, which, combined with the continuing Austrian artillery fire, convinced Von Moltke that he may had underestimated Benedek. With his reserves of infantry and cavalry stuck on muddy approach roads behind the lines, Moltke did not have the resources to complete the encirclement at Königgrätz and stopped the pursuit. The Austrian cavalry broke off at this point and the battle ended at 9pm.

Most of Benedek’s army escaped across the Elbe in the night, but the Austrian losses were high – 44,000 men in the course of the day, compared with Prussian losses of just 9,000. The Austrian Army that retreated to Vienna was very weakened and the Austrian emperor had no option but to agree to an armistice on 22 July 1866, and three weeks later sued for peace. Bismarck used the victory to further his ambitions, abolishing the German Confederation and forming the North German Federation that excluded Austria and her allies in Germany. Its position as the dominant power in continental Europe was confirmed five years later with an emphatic victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the resulting unification into a united Germany.

Today Königgrätz is a fascinating battlefield to visit. Situated 125km to the East of Prague in the Czech Republic, it is about an hour and a half drive from the centre of the Czech capital. The battlefield is relatively undeveloped and one can very quickly gain an understanding of the terrain and the flow of the battle. There is a small museum and visitor centre that provides useful orientation and an observation tower. These are both located together just outside the village of Chlum, right at the heart of the battlefield and on its highest spot. The tower affords panoramic views of the area and from which one can appreciate the scale of the battle and the influence of the terrain.

The actions of many regiments and individuals are marked with memorials across the battlefield. These include a monument erected at the location where Captain August von der Groeben and his ‘Battery of the Dead‘ conducted their heroic but doomed rearguard action.

The Sweipwald is full of memorials to both sides, placed here both by regiments in memory of fallen comrades and families for loved one. As one walks through the woods it is easy to envisage how this part of the field became a bloody killing ground as the combat ebbed and flowed. But today it is peaceful and serene, and judging by my experience very little visited, as we were the only people in the woods on a fine July afternoon last year!

The impact of this battle was felt long after it finished. Bismarck’s vision of a dominant and imperial Germany of course came to fruition, and ultimately led to Germany’s role in helping to start the First World War, the legacy of which had a continuing impact throughout the subsequent history of the twentieth century. It is perhaps worth reflecting on what might have happened had there been an Austrian victory on 3 July 1866. Would it have resulted in a ‘Grossdeutschland’ that would have joined the German states in a less aggressive and less martial multi-national Empire, leading to a more peaceful Europe and avoiding the two world wars of the twentieth century? This is of course speculation but what is very clear is how important this short war, and the little known battle of Königgrätz were in actually shaping the European history we know today.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks. Glad you liked the post.

LikeLike

Is there someone I may speak to about using these photos for a publication?

LikeLike

Hi. Which photos are you interested in using? The photos of the battlefield today are mine, and I would happily share them, subject to understanding where/how they are to be used. The other images have the sources underneath them. Do let me know your requirements. If you want to use mine I can provide high quality copies.

LikeLike

Very interesting article. I have a certificate awarded to my great grandfather, Hermann Schede, for his dutiful participation in the battle. It says he was awarded a bronze remembrance cross. (We do not have that) He was a foot soldier of the 12th Company 4th Magdelburg Infantry Regiment. Awarded in Wittenburg 20th of September 1866.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Cherie. Pleased you found it interesting. I am fascinated that you know so much about your great grandfather’s participation in the battle. I have not come across anyone else with such a personal connection with this battle. His regiment were part of the 14th Brigade, of the 7th division, of the Prussian IV Corps and were at the heart of the attack on the Sweipwald! Do you know any more about him?

LikeLike