A few weeks ago I was lucky enough to take a trip to Poland, and to visit two of its flagship museums. Both located in the country’s capital city, they address some of the major themes in Poland’s traumatic and turbulent history.

The first was POLIN:Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Its subject matter is exactly what one would expect from its title and the scope and scale of its content is vast. It was awarded European Museum of the Year 2016 and it is easy to understand why. It follows the story of Poland’s Jewish population and explains how Jews have been an integral part of the country for a thousand years.

The challenge facing the designers of this museum was to create a meaningful and engaging place with very few original artefacts. The harsh reality of Poland’s history is that successive invasions and occupations have taken a toll on its physical history. It is conservatively estimated that a quarter of a million works of art, a huge proportion of Poland’s cultural heritage, were looted by the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union during the Second World War and few have ever been recovered. However, once inside POLIN it is very clear that this challenge has been met and overcome very effectively,with clever and innovative interpretation filling the gap.

The museum’s core exhibitions are succinctly described on the museum’s website as follows:

The exhibition is made up of eight galleries, spread over an area of 4000 sq.m., presenting the heritage and culture of Polish Jews, which still remains a source of inspiration for Poland and for the world. The galleries portray successive phases of history, beginning with legends of arrival, the beginnings of Jewish settlement in Poland and the development of Jewish culture. We show the social, religious and political diversity of Polish Jews, highlighting dramatic events from the past, the Holocaust, and concluding with contemporary times.

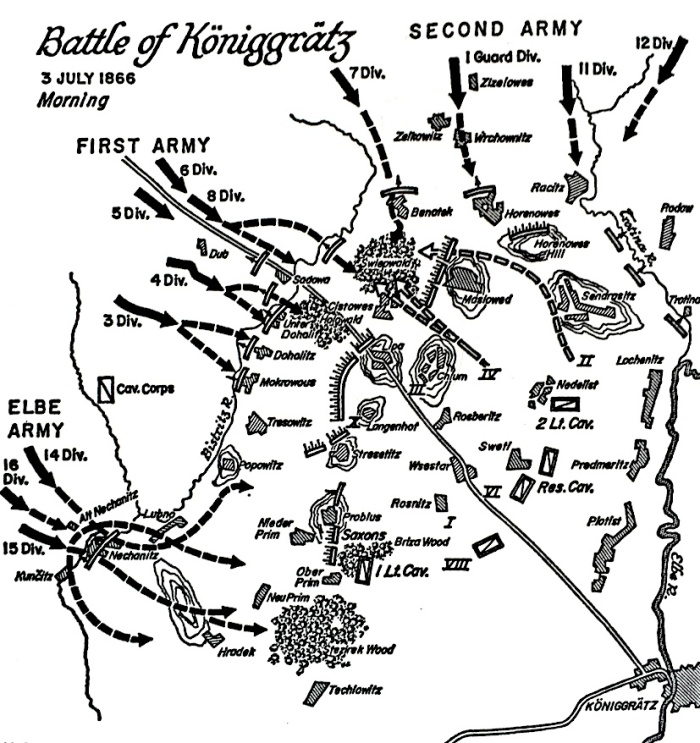

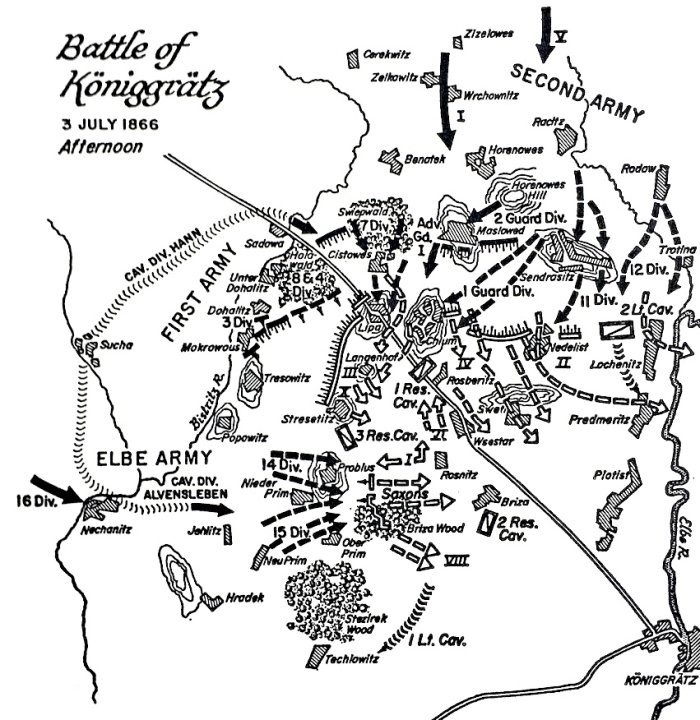

Each of these eight galleries has its own style and method of storytelling, and a wide range of techniques are used. From a beautifully animated 3D map of Krakow and Kazimierz in the 16th Century, through a stunning recreation of the painted ceiling of the wooden synagogue from Gwoździec, the galleries are a feast for the eyes. But of course the Jewish story has a much more traumatic side to it, as indeed does that of Poland. The fourth of the eight galleries reflects on how at the end of the eighteenth century, Russia, Prussia and Austria partitioned Poland and how during the next century Poland’s Jews, and for that matter the rest of the Polish population, were divided to live dispersed under each of the three powers.

This is followed by ‘the Jewish Street’ a reconstruction of a scene from the Jewish district of Warsaw in the 1920/30s and tells the story of the brief post-First World War resurgence of Jewish nationalism in Poland during this period, before the savage repression of the Nazi Occupation during the Second World War. The museum itself stands in the centre of what was Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto, opposite the memorial to the Ghetto Heroes of the 1943 Ghetto Uprising which was erected in 1948. The museum therefore unsurprisingly covers in detail the impact of the Holocaust. It chronicles its cruel consequences for Poland’s Jewish population and is told with no ‘punches pulled’. The visual impression of the Holocaust gallery is dark and oppressive as one would expect given that more than three million Polish Jews were eventually murdered during this period. The galleries finish with the opportunity to reflect on the thousand years of Poland’s Jewish history and what that memory means for Polish Jews today.

POLIN is a monumental museum in more than one way. As a pure museum it is enormous in its scope, making it the sort of place one would need to visit time and again to really appreciate the depth of content. But it is also a memorial to the human spirit and its ability to survive through adversity and emerge, battered and brutalised, despite the most awful of conditions. And it is this human spirit that is also celebrated in the second of the museums I wish to consider.

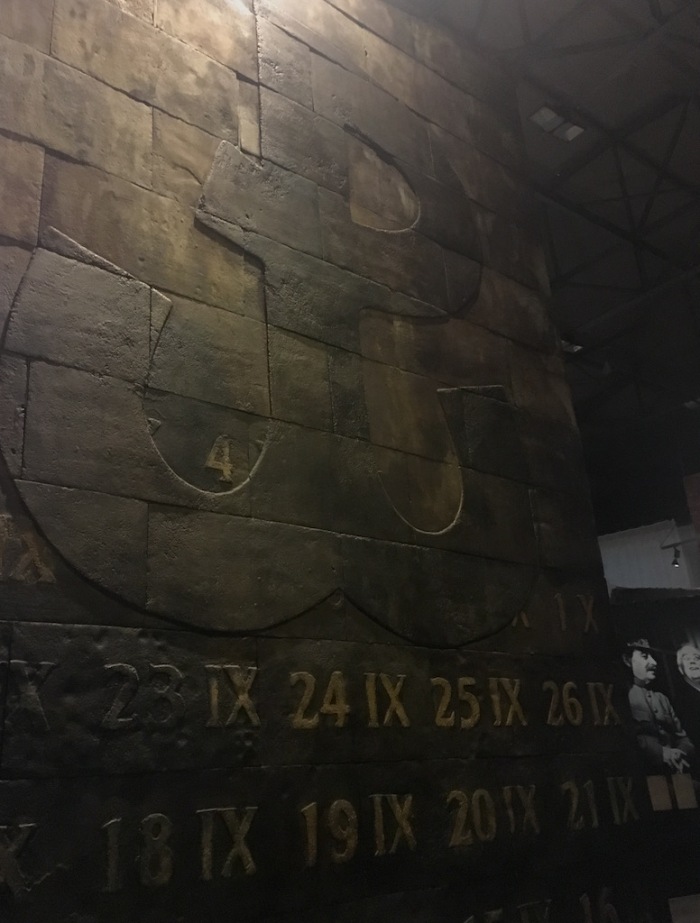

The Warsaw Rising Museum, in contrast to POLIN, tells the story of a much shorter, but equally emotive, period of Polish history, the Warsaw Rising of 1 August to 2 October 1944. Housed in a building that formerly served as the power station for the Warsaw tram system, its exterior is imposing, and topped with a modern observation tower affording views over the city.

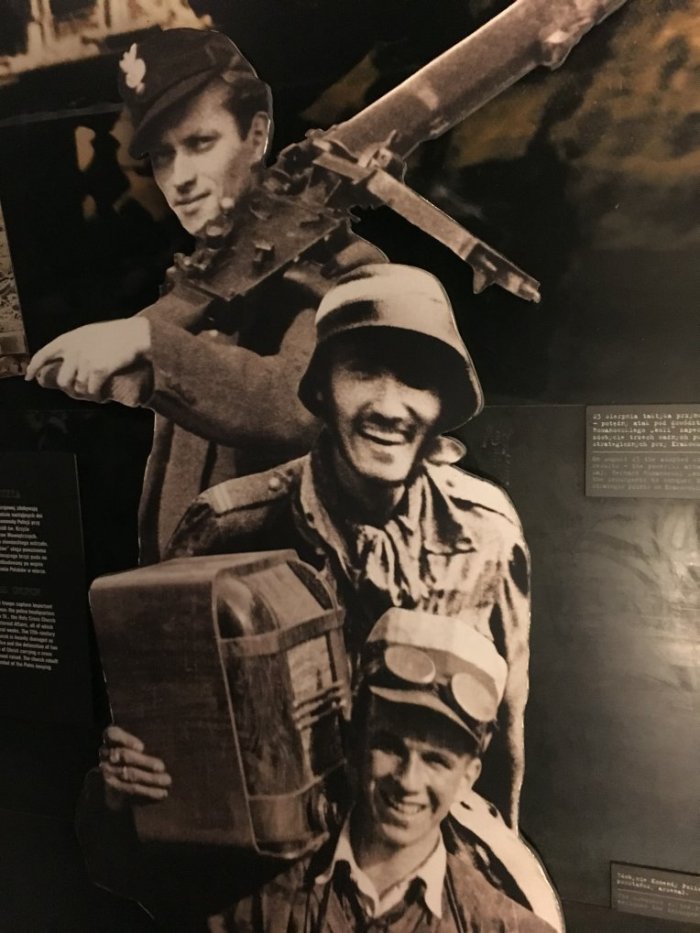

The Museum was opened on 31 July 2004 on the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the fighting in the city that marked the start of the Rising. The exhibitions within chart the hardships of everyday life before and during the Rising, and the appalling conditions the people of Warsaw lived under during the occupation. It is also a tribute and memorial to those who fought and died for a free Poland. The interpretation is excellent with great use of images and sound, as well as film that was amazingly recorded during the Rising. At the very heart of the Museum is a steel monument which stretches from bottom to top linking all floors of the building. Inside the memorial one can hear the sound of a heartbeat which symbolises the beating heart of fighting Warsaw in 1944 and is a rather eerie presence throughout the museum.

The collection of artefacts dispersed within the museum includes uniforms worn by the combatants, the weapons they were armed with and, very evocatively, the original named red and white armbands worn by some of the fighters. There are also sections that look at many different and more unusual aspects of the occupation and Rising. These include the cultural activities that continued despite the fighting and the role of young boys and girls who carried out the very dangerous role of postmen and women for the Field Postal Service by carrying messages around the city.

Like POLIN the execution of this museum is excellent. The story is told using a wide range of interpretation methods, the scope of the content is huge, and again a single visit does not do the content justice. It is also very clear how important to the story of modern Poland the Rising is, and how revered its veterans are held within the country.

Before I visited Warsaw I had a rudimentary understanding of Polish history and its place, by virtue of its geography, as a ‘buffer nation’ between two much more powerful, and at times aggressive, neighbours. I knew of its Jewish past and the appalling atrocities inflicted on its Jewish citizens during the Holocaust, and I was aware of the wartime Rising. What I was not aware of was the detail, in particular the myriad personal stories and tragedies therein. Both these museums help the visitor to access and understand these stories and I came away from my visits much better informed. I am now also much better able to understand the huge national pride that Poland as a nation and its people display, and the important role these museums are playing in immortalising its turbulent history.